#Broad-Billed Moa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

A lithograph from volume 7 of Transactions of the Zoological Society of London (1870) depicting the skull of a broad-billed moa. This species was found on both New Zealand’s North and South Islands, as well as neighboring Stewart Island. [ x ]

#historical art#historical illustration#Broad-billed moa#Stout-legged moa#Bird#EX#Art#Skeletal remains

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

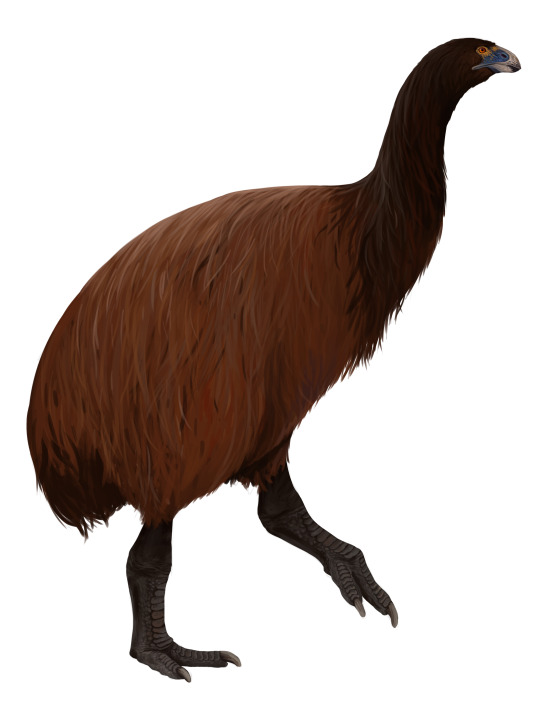

Euryapteryx curtus

By Jack Wood

Etymology: Broad Lacker of Wings

First Described By: Haast, 1874

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Palaeognathae, Notopalaeognathae, Tinamiformes + Dinornithiformes Clade, Dinornithiformes, Emeidae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 130,000 and 600 years ago, from the Chibanian of the Pleistocene and the Holocene

The Broad-Billed Moa is known from all over the New Zealand islands, especially lowland dunes, forests, shrublands, and grasslands

Physical Description: The Broad-Billed Moa was a large, bulky dinosaur, covered in very shaggy feathers all over its body. It had a long neck, ending in a small head, with a wide bill - hence the name! It also had very sturdy, thick feet. These birds - like all Moa - entirely lost their wings, giving them a fairly boxy appearance. Their shaggy feathers would have been somewhat monochromatic, as well. These birds would grow up to one meter long, and females of this species were probably larger than the males.

Diet: The Broad-Billed Moa was an herbivore, grazing on a wide variety of plant material (including grass).

By Michael B. H., CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: These birds would have been somewhat slower animals, spending most of their time lumbering about the coasts and plains of New Zealand, and eating most of the plant material they could find. They probably would eat as much food as they could, using their broad bills to grab more food and to not selectively browse on specific plants. They also probably herded together, forming loose groups as they roamed across the fields for food. These birds probably took care of their young, though how and to what extent is uncertain as it varies quite a bit amongst other ratites.

Ecosystem: New Zealand in the Pleistocene and Holocene was an extremely unique ecosystem, one of the few places in the world largely free of mammals during the Cenozoic. This meant that birds tended to fill the niches of mammals, doing things that ancient non-avian dinosaurs used to do. In addition, the lack of mammalian predators allowed for extensive diversification of birds even within their usual niches - the weird New Zealand Wrens, for example, are some of the most unique types of perching birds.

By Scott Reid

This environment consisted of many other Moas, such as Pachyornis, Anomalopteryx, and Dinornis just to name a few; the aforementioned Kiwi bird; and other large weird birds like the Kākāpō and Kea and Kākā, other parrots, other passerines, cuckoos, swifts, water birds, owls, and more. During the days of the Moa, there was also the Haast’s Eagle, a large predator of Moa that would have been a huge thorn in the side of the Broad-Billed Moa. Also, there were Adzebills, weird relatives of living cranes that also filled the large land bird niche but with pointier beaks. In short, this was a modern-day Jurassic park, prior to being screwed up by human colonization and hunting, which drove many of these unique animals to extinction in the early modern period of history.

Other: For a long time, Moa like Euryapteryx were thought to be closely related to the other weird ratite of New Zealand, the Kiwi. However, later research revealed they were more closely related to the Tinamous of South America. What this shows is that, at some point, relatives of the Tinamous flew over to New Zealand, and colonized the island before becoming large, flightless weirdos.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Bunce, M., T. H. Worthy, M. J. Phillips, R. N. Holdaway, E. Willerslev, J. Haile, B. Shapiro, R. P. Scofield, A. Drummond, P. J. J. Kamp, and A. Cooper. 2009. The evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa and New Zealand Neogene paleogeography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106:20646-20651

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003). "Moas". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. 8: Birds I: Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

Gill, B. J. (2010). "Regional comparisons of the thickness of moa eggshell fragments (Aves: Dinornithiformes)". Records of the Australian Museum. 62: 115–122.

Lambrecht, K. 1933. Handbuch der Palaeornithologie. 1-1024

Milkovsky, J. 1995. Nomenclatural and taxonomic status of fossil birds described by H.G.L. Reichenbach in 1852. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 181:311-316

Owen, R. (1846). A History of British Fossil Mammals and Birds. London, UK: John Van Voorst.

Worthy, T. H., and R. N. Holdaway. 1994. Quaternary fossil faunas from caves in Takaka Valley and on Takaka Hill, northwest Nelson, South Island, New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 24(3):297-391

Worthy, T. H., and R. N. Holdaway. 1996. Taphonomy of two holocene microvertebrate deposits, Takaka Hill, Nelson, New Zealand, and identification of the avian predator responsible. Historical Biology 12(1):1-24

Worthy, T. H. 1998. A remarkable fossil and archaeological avifauna from Marfells Beach, Lake Grassmere, South Island, New Zealand. Records of the Canterbury Museum 12:79-176

Worthy, T. H., and J. A. Grant-Mackie. 2003. Late-Pleistocene avifaunas from Cape Wanbrow, Otago, South Island, New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 33(1):427-485

Worthy, T. H.; Scofield, R. P. (2012). "Twenty-first century advances in knowledge of the biology of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes): a new morphological analysis and moa diagnoses revised". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 39 (2): 87–153.

#Euryapteryx curtus#Euryapteryx#Broad-Billed Moa#Moa#dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Dinosaurs#Stout-Legged Moa#Coastal Moa#Palaeognath#Terrestrial Tuesday#Herbivore#Australia & Oceania#Quaternary#paleontology#Palaeoblr#prehistory#Birblr#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neimongosaurus yangi

Xixiasaurus henanensis

Broad-Billed Moa (Euryapteryx curtus)

Shri devi

For this Theropod Thursday, I’d like to spotlight Funkmonk (Michael B. H.) a paleoartist from Wikipedia. I literally have no idea who this person is, I can’t find anything about them, but they’ve done some good art for a great cause. I think that putting scientifically-accurate reconstructions on wikipedia pages does a lot to update the public perception of extinct animals.

266 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The turtle-jawed moa-nalo (Chelychelynechen quassus) was a large flightless goose-like duck from the Hawaiian island of Kaua‘i. About 90cm tall (3′) and weighing around 7kg (15lbs), these birds and their relatives were descended from dabbling ducks and existed on most of the larger Hawaiian islands for the last 3 million years or so -- before going extinct around 1000 years ago following the arrival of Polynesian settlers.

Chelychelynechen had an unusually-shaped bill, tall and broad with vertically-oriented nostrils, convergently similar to the beak of a turtle. It would have occupied the same sort of ecological niche as giant tortoises on other islands, filling the role of large herbivore in the absence of mammals.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#moa-nalo#chelychelynechen#turtle-jawed moa-nalo#anatinae#anatidae#duck#anseriformes#galloanserae#bird#hawaii#kauai#island weirdness#holocene extinction#i want one

607 notes

·

View notes

Text

My favorites (dodo and thylacine) were already mentioned but here are some more:

- Gastric brooding frog

- Caribbean monk seal

- Xerces blue butterfly

- Toolache wallaby

- Paradise parrot

- Honshu wolf

- Bulldog rat

- Laughing owl

- Warrah

- Broad-billed parrot

- Kawekaweau

- Rodrigues solitaire

- Upland moa

- Meiolania

- Balearic Islands cave goat (Myotragus)

- Thylacoleo

- Thylacosmilus

- Megalania

So the title of my extinct animals project will be 'The Erased Creature Series' and I'm still looking for animals to feature!

I need 18 more so if anyone can give me an extinct species or five then I'll love you forever!

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is the procedure for making a trade licence? What are the required documents to get it?

Trade Licence – Permission or License issued by the municipal corporation as permission to carry on a particular business at a particular address for a specified period of time after ensuring that the citizens are not adversely affected either as health hazard or nuisance created by the business carrying the trade is called a trade license.

Essentially, it is managing a business in a specific locality. The trade license is an instrument for ensuring that the manner and locality in which the business is being carried on in adherence to the relevant rules, standards and safety guidelines.

The state government laid down the concept of Trade License to monitor and regulate the trade within a city. The municipal corporation of the particular place where the business is located issues the trade license. Substantial penalty and subsequent prosecution may be given as a result of unauthorized trade, which is an offense and hence, the owner of the businesses must obtain a trade license if required. An application in this regard must be filed before the commencement of the activity of business or trade.

Once a trade owner gets the License, it should be renewed periodically. Annual renewal of the License is required on a regular basis after the issuance of the License. For the renewal of the Trade License, the Application required for renewal must be filed at least 30 days before the expiry of License.

The limitation to the trade license is that no kind of property ownership is transferred with the Trade License.

Since, it is an important part of public interest, to avoid bulking of license form, it has been divided into three categories:

1. Industries license: small, medium and large-scale manufacturing factories

2. Shop license: Dangerous and Offensive trades like a sale of firewood, cracker manufacturer, candle manufacturer, barbershop, dhobi shop etc.

3. Food establishment license: Restaurants, hotels, food stall, canteen, the sale of meat & vegetables, bakeries etc.

But not everyone can get the trade license issued, certain criteria for eligibility for applying for the trade license is laid down:

1. The age of the owner must be above 18 years.

2. No criminal records must be there.

3. All permission must be obtained already.

ADVANTAGES

There are four broad advantages of Trade Licence

Legal Protection: Getting a Trade License issued, may lead to penalties based on the nature and duration of the company as it ultimately classifies the business as illegal. The main reason is to keep in check unethical and illegal trade practices and check adherence to the applicable rules, standards, and safety guidelines. It provides protection to owners of business against any certain types of liability and limits it to the trade or business liability. Not getting a trade license can lead to the imposition of penalty and punishment and, ultimately, closing down of business. When you have a trade license, you will be liable to enjoy the rights of bragging it.

Implies Competence: Increase in commercial setup for India, the main concern was to avoid commercial activities running in a residential area or commercial area and creating a health hazard and hence, the initiative of Trade license was put forward to keep a check on such activities. No municipal authority has the right to shut down the activity without proper notice and time for adherence with the presence of a Trade License. This instills competence within entrepreneurs.

Goodwill, Public and Personal Benefit: We compare licensed and non-licensed businesses, it is effortless to decide which business we will choose, which is basically one of the most significant advantages of a Trade license, it creates a better image and goodwill of the business which attracts more customers and hence more business than an unregistered entity. Goodwill attracts various investment groups and other business organizations, helping in growing the prestige of the firm.

License separates personal identity with that of business identity and limits the legal liability, it does the same with personal and business finance by separating them.

DOCUMENT REQUIRED

Signed copies of

1. Pan Card of company, LLP, or Firm.

2. Canceled Cheque or bank statement of the entity.

3. COI along with MOA and AOA of the company.

4. Proof of Premises of the establishment in the form of Sale Deed, Electricity Bill/water bill and NOC from the owner.

5. Colour Photograph, ID Proof, Pan Cards along with Address Proof of all Directors/ Partners.

6. Front-Facia Photograph of the entity

PROCESS OF REGISTRATION / RENEWAL

Form 353 is to be duly filled and submitted along with all the above-mentioned documents to the Municipal Corporation after the type of Trade License is finalized.

The Application for the same is to be made to the State or Municipal Corporation under whose local jurisdiction does the business lie, which is different for different states.

Trade License can be downloaded online after approval, the processing time for which on an average is 10-15 days or might differ for different states.

January 1st to March 31st is the time usually when the license renewal applications are made and has to be renewed annually since the validity of the License is of one year.

As mentioned above, the Application of renewal should be made 30 days before the expiry of the License, delaying might lead to fine according to the rules and regulation of the issuing authority and the State.

Documents that are needed for the renewal of the Trade Licence are–

1. Original copy of the trade License;

2. Previous year challan;

3. The latest Property tax paid receipt.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

1. Municipal Corporation issues the trade license exclusively for trade or business and cannot be used for any other purposes.

2. Every State of India has a different set of rules and regulations for the issuance of a Trade Licence.

3. The nature of the business decides the fee structure for the issuance of a Trade license.

4. A business granted with this License will enjoy more considerable goodwill than an unregistered entity and subsequently attracts more customers and investors.

About Us

LetsComply is a full service law firm and is the best platforms for all your Legal, Finance and Taxation needs. Letscomply is one of the leading law firms in India and having team comprises of Corporate Lawyers, Company Secretaries, Chartered Accountants, Cost Accountants, IP Attorneys, and Management Experts with rich experience in their respective filed. We believe in long-term alliances for mutual growth.

For More Information and Contact US: https://www.letscomply.com/trade-licence/

Contact Us:

+91-97-1707-0500

https://www.letscomply.com/

SERVICES PROVIDED BY US:

Foreign Investment in India| Setting-up of Business in India |Virtual CFO| Virtual General Council| NCLT Matters | IBC matters| Income Tax | GST Registration & Returns |Trademark registration | Company Registration | LLP Registration |NGO| Company Annual Compliances | Drafting & Vetting of Agreements |Opinion & Advisory on Different Issues| FSSAI Licenses| ESI & EPF | ISO certification |Shop & Establishment Registration |MSME Registration| SEIS/MEIS Services| DGFT| Legal Notices.

0 notes

Text

Warrantless surveillance law proves its time to take privacy into our own hands

David Gorodyansky Contributor

David Gorodyansky is the CEO and co-founder of AnchorFree.

More posts by this contributor:

This is the future if net neutrality is repealed; the creeping, costly death of media freedom

The warrantless surveillance law, otherwise known as Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, gained mass attention back in 2013 when Edward Snowden leaked information that the NSA was using it to spy on Americans’ text messages, phone calls, emails and internet activity — all legally, and without warrants.

That bill has been passed by the U.S. Senate for another six years and has now been signed into law by President Trump — a further extension of what should be an Orwellian cliché but remains quite real.

Naturally, this has caused quite the uproar over not so much the intent of Section 702, but rather how this law could (or will) be interpreted. The act allows the NSA to monitor the communications of foreigners located outside of the U.S. to gather foreign intelligence — which is the law’s intended purpose.

These practices have already hurt our image abroad when it was discovered that the NSA spied on Angela Merkel and the former president of Brazil. However, the domestic use of the law rightfully has caused many to fear further overreaching of the NSA into the lives of American citizens.

And much of said data has reportedly been made available to different U.S. intelligence services.

“Because of these votes, broad NSA surveillance of the Internet will likely continue, and the government will still have access to Americans’ emails, chat logs, and browsing history without a warrant,” said David Ruiz, a staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Because of these votes, this surveillance will continue to operate in a dark corner, routinely violating the Fourth Amendment and other core constitutional protections.”

Senators Rand Paul (R-KY), Michael Lee (R-UT), Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Ron Wyden (D-OR) agree, presenting a bipartisan letter to colleagues stating that “this bill allows an end-run on the Constitution by permitting information collected without a warrant to be used against Americans in domestic criminal investigations.”

This insidious law that allows such an overarching, predatory invasion of our personal lives has been given new life as quickly and quietly as possible. Privacy advocates are loudly publicizing their disgust — but the media has little time to discuss what amounts to a borderline limitless invasion of our privacy.

“Lawmakers have a responsibility to make sure Americans understand what the impact will be of the laws they pass,” Wyden wrote in The Cipher Brief. “Having support for the laws you pass is what makes a government legitimate.”

Section 702’s intended purpose is to protect American soldiers, keep U.S. decision-makers informed about the intentions of adversary nations and help federal agents detect and prevent terrorist attacks on U.S. soil. However, the evaluation of 160,000 emails and instant messenger conversations collected under Section 702 between 2009 and 2012 (leaked by Snowden in 2013) showed that 90 percent of them were from online accounts that were not foreign surveillance targets, according to The Washington Post.

And nearly half of those belonged to U.S. citizens or residents. That’s tens of thousands of emails from regular people, collected without our approval, say-so or, indeed, knowledge.

This alone indicates that this law is in need of serious reform to protect the privacy of American citizens; those citizens deserve to understand what information the NSA is collecting from them.

It’s time to take this into our own hands. Privacy solutions and applications have been skyrocketing in demand, and with news that this law will likely prevail for another six years — as well as the recent scrapping of net neutrality — that demand is only going to increase as people seek to take their online security and privacy into their own hands.

You also may say that this simply can’t happen to you — that such a world doesn’t exist in America, that your door is open and you have nothing to hide. I like to say that we have nothing to hide, but a lot to protect. Think about your health, wealth and communications with family; you probably don’t want a bunch of guys in a room reviewing everything you write to your doctor or your loved ones.

Modern society may seem impenetrable to such terrifying futures until you look at China’s social “proof” system. The social credit system, as the government calls it, refers to “raising the awareness for integrity and the level of credibility within society,” which is entirely based on big data from both private and public sources. By 2020, they hope to have an entire credit system based on the whims of private companies and how “self-restrained” citizens are online. This is to say nothing of the Identity Brokers that for a small fee likely have your name, date of birth, address and every crime you’ve committed.

Civilized society generally operates on not having the government censor their populace as has recently happened in Iran. But the most powerful censorship is that which is caused by the cages we build around us. As we watch ads track us around the internet, click to “like” something on Facebook and retweet content, someone, somewhere is watching. And with enough data, that can be used to cause us to act in a particular way. It can be used to subtly nudge us or brutally shove us.

We cannot have freedom without the right to privacy. That’s why the United Nations lists both Internet Freedom and Online Privacy as basic human rights. As we reflect on the future we want to build for ourselves and future generations, let’s work on a future of freedom and the right to privacy versus one of censorship and big brother looking over our shoulder.

More From this publisher : HERE ; This post was curated using : TrendingTraffic

=> *********************************************** See More Here: Warrantless surveillance law proves its time to take privacy into our own hands ************************************ =>

Sponsored by E-book Vault - Free E-book's

=>

This article was searched, compiled, delivered and presented using RSS Masher & TrendingTraffic

=>>

Warrantless surveillance law proves its time to take privacy into our own hands was originally posted by A 18 MOA Top News from around

0 notes

Text

Euryapteryx curtus

By Jack Wood on @thewoodparable

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Euryapteryx curtus

Status: Extinct

First Described: 1846

Described By: Owen

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Palaeognathae, Notopalaeognathae, Tinamiformes + Dinornithiformes Clade, Dinornithiformes, Emeidae

Euryapterux is another single-species Moa, very closely related to the Eastern Moa from yesterday. It’s common name is the Broad-Billed Moa, and it lived on both the North and South islands of New Zealand. It lived from the Chibanian of the Pleistocene to the Holocene, from about 130,000 years ago to 500 years ago. It lived mainly in coastal locations which may be an indication of niche partitioning between the Moa in New Zealand during the Holocene. It’s broad bill would have allowed it to eat a wide variety of plants all at once, indicating it wasn’t a very selective browser. The females were, as usual, much bigger than the males, and it had very thick and stout legs and a bulky body.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broad-billed_moa

http://www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/e/euryapteryx.html

#euryapteryx#broad billed moa#moa#bird#dinosaur#birblr#palaeoblr#palaeognath#euryapteryx curtus#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍

55 notes

·

View notes

Link

Time for the next round!!! It’s time to vote in the BIRD SPECIES that WILL be the competitor in this year’s Dinosaur March Madness!!!! All eligible species ARE LISTED. Please READ the below information so that you make an informed voting choice! You have through February 4th!!!!!!!!

HIGHLIGHTS & INELIGIBLES

Giant Moa

The giant moa were two of the largest known moa - a group of large flightless birds from New Zealand, closely related to modern tinamous, which mainly fed on low lying vegetation in their environment. They were some of the dominant herbivores of New Zealand, and only went extinct a few thousand years ago due to human hunting. The two species are the North Island Giant Moa and the South Island Giant Moa. They differ primarily in that they come from different islands of New Zealand - with the North Island Giant Moa coming from the northern island, and the South Island Giant Moa coming from the southern island, but in addition to this, the South Island Giant Moa was also the biggest known moa, and the tallest known species of bird. List of ineligible candidates: None

Ducks, Geese, & Relatives

The anatids - ducks, geese, swans, and their relatives - are waterfowl that feature heavily in everyday life. Primarily herbivorous, they feed on water plants in a variety of habitats, such as lakes, ponds, and wetlands. They have webbed feet, short pointed wings, and bills that are usually flattened. Some species, the mergansers, are piscivorous, using serrations on their bills to catch fish. Many of them undergo very large annual migrations, and some have been domesticated. They come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, with many have long slender necks, and most also having short and strong legs for swimming - though they’re relatively awkward walking around on land. Highlighted species include the Hooded Merganser (a diving duck in which the male has a conspicuous black-and-white head crest), the Kauaʻi Mole Duck (an extinct Hawaiian duck that had poor eyesight, likely foraging on land by smell and touch), the Northern Shoveler (an unmistakable duck with a spatula-like bill, very specialized for feeding on plankton), and the Trumpeter Swan (the largest living waterfowl). List of ineligible candidates: None

Hummingbirds

Hummingbirds are a group of highly specialized birds that include some of the most spectacularly colored and smallest dinosaurs known. They have extremely strong hearts and wings specialized for hovering, which they can flap at very high speeds to allow for them to hover and procure nectar from flowers much like bees and butterflies—in short, they’re dinosaurs that convergently evolved with insects. Males are, typically, smaller than females in the smaller hummingbirds, and larger than females in the larger hummingbirds. They have the highest metabolism of any animal to support their rapid wing beats. Their colors serve to compete for both territory and mates, and is primarily brilliantly colored in male hummingbirds - and they even use the sun to enhance their sheen. Highlighted species include the Marvelous Spatuletail (in which the males have a pair of extremely long tail feathers with expanded tips), the Sword-billed Hummingbird (which has a bill longer than the length of its body), the Xanthus’s Hummingbird (which has white “eyebrows” and is found only in Baja California), the Long-billed Hermit (in which the males have dagger-like bills for fighting), and the Anna’s Hummingbird (in which the males perform diving displays reaching 385 body-lengths per second and make sounds using their tail feathers). List of ineligible candidates: Bee Hummingbird, Vervain Hummingbird

Turacos

Turacos are a group of poorly flighted African birds that feature a wide variety of weird plumages and pigmentations, including some of the only truly green pigments found in animals (rather than green due to iridescent sheen and/or combinations of other pigments). They evolved perching ability similar to, but independently from, perching birds and parrots, making their feet an interesting example of convergent evolution. Though they are weak fliers, they do run about the trees very rapidly, and make a lot of noisy alarm calls to each other. They are some of the weirdest and prettiest known birds, in terms of both names and plumage. Highlighted species include the Great Blue Turaco (the largest species of turaco, with bright blue plumage, yellow tail feathers, an interesting black tufted crest on its head, and a red band on its beak), the Guinea Turaco (an actually true green bird with a fluffy crest on its head and bright red rings around its eyes), the Bare-Faced Go Away Bird (which not only has one of the best names of any dinosaur, but also has a literal bare face and it is very noisy and restless), and the Red-Crested Turaco (which is very small, true green, and has a red crest as well as tiny wings that are red underneath—seriously, so smol). List of ineligible candidates: None

Cranes

Cranes are a group of birds that tend to be large or very large in size, and often quite tall. They have long legs and necks and often nest near water. Some species migrate long distances. Cranes are omnivores and forage on the ground or in water. They maintain strong pair bonds, often mating for life. New pairs engage in elaborate dances prior to mating. Most species have a long, coiled windpipe that allows them to produce loud, trumpeting calls. Highlighted species include the Grey Crowned Crane (known for having a crown of stiff golden feathers on their heads and a red inflatable throat pouch), the Siberian Crane (one of the rarest cranes, almost pure white except on places along the wings only visible in flight, males and females are known for streaking mud through their feathers for display in breeding season), and the Sandhill Crane (known for soaring flight and one of the longest fossil histories for any living bird, with the oldest fossil being 2.5 million years old). List of ineligible candidates: Wattled Crane, Blue Crane, Demoiselle Crane, Red-Crowned Crane, Whooping Crane, Common Crane, Hooded Crane, Black-Necked Crane, G. afghana, G. antigone, G. nannodes, G. haydeni, G. penteleci, G. bogatshevi, G. latipes, Maltese Crane, G. pagei, G. primigenia

Auks

Auks are a group of seabirds that use their wings to swim and dive underwater where they feed on fish and plankton. This makes them similar to penguins, despite not being closely related. (Indeed, the term “penguin” was actually first applied to auks.) Unlike penguins, auks live in the Northern Hemisphere and all extant species can fly. However, they need to flap very quickly during flight due to their short, paddle-like wings. Auks spend most of their lives at sea, typically only coming ashore during breeding season. They often mate for life and generally nest in large colonies. Highlighted species include Miomancalla (a prehistoric flightless relative of auks and the largest known shorebird), the Atlantic Puffin (known for its bright orange bill and spends a large portion of its time in open ocean), the Ancient Murrelet (which spends less time on land than any other bird, with juveniles making their way to the sea at only 1-3 days old), the Crested Auklet (known for its strange forehead crest and smelling strangely like citrus), and the Dovekie (a very small auk that is completely adorable). List of ineligible candidates: Great Auk

Herons

Herons are a group of predatory wading birds with long legs, long bills, and long necks. Members of this group that have mostly white plumage are often known as “egrets”. Herons typically hunt by standing and waiting for prey to come within reach, before spearing the hapless victim with their beak. Most species feed primarily on fish, but they will generally eat any animal small enough to swallow. Herons possess specialized down feathers that grow continuously and disintegrate at the tips, forming a powder that helps the birds remove grease from their plumage while preening. Many species grow ornamental plumes during breeding season, and they generally nest in trees (though the well-camouflaged bitterns tend to nest in reed beds instead), sometimes in large colonies. Unlike many other long-necked birds (such as storks and cranes), herons fly with their necks folded back rather than outstretched. Highlighted species include the Boat-billed Heron (has a large, broad black beak for feeding on shrimp and small fish), the Eurasian Bittern (known for communicating with very deep calls and camouflaging itself by freezing with its bill in the air to mimic reeds), the Green Heron (known for keeping its neck close to its body until it strikes at prey like a harpoon, as well as using small objects such as feathers to bait fish), and the Goliath Heron (the largest heron in the world, almost never moves away from water). List of ineligible candidates: None

Hawks, Eagles, & Relatives

The majority of diurnal birds of prey are members of Accipitridae, including kites, hawks, eagles, and Old World vultures. They are found on every continent except for Antarctica and have adopted a wide variety of lifestyles. Collectively, they are known to prey on everything from insects to large mammals such as deer. They generally have extremely powerful feet and large talons that they use to capture and kill prey. Accipitrids have extremely keen eyesight, able to perceive objects at higher acuity from far greater distances than humans can. In most species, the females are larger than the males and mated pairs often pair for life. Highlighted species include the Palm Nut Vulture (unusually for an accipitrid, it primarily feeds on oil palm fruit), the Haast’s Eagle (a massive extinct eagle that preyed on moa, and believed to be the Pouakai of Maori legend), the Swallow-tailed Kite (a very graceful flier known for its long, forked tail and nests in wooded areas or near wetlands), the Steller’s Sea Eagle (one of the largest eagles and feeds primarily on fish, though it is known to prey on seabirds as well), and the Harris’s Hawk (one of the few raptors that hunts in packs, popular in falconry due to its intelligence). List of ineligible candidates: Harpy Eagle, Bearded Vulture

Typical Owls

Strigidae includes most modern owls other than barn owls and their close kin. Owls are primarily nocturnal birds of prey. The long feathers on their face form a disk that helps collect sound and direct it towards their ears. They use their large eyes and sensitive hearing to hunt at night, and most species have specialized wing feathers that allow them to fly silently while approaching prey. They are generally cryptically colored to help them avoid larger predators and smaller birds that may harass them during the day. Females are usually larger than males, and most species seem to maintain long-term pair bonds. Highlighted species include Ornimegalonyx (an extinct genus believed to be the largest owl to exist), the Snowy Owl (a popular and well recognized owl known for its white plumage, was one of the original species of birds described by Linnaeus himself), the Eurasian Eagle Owl (one of the largest living and most widely distributed species of owl, has prominent ear tufts), the Northern White-faced Owl (nicknamed the “transformer owl” for its defensive behaviors such as puffing its feathers when facing a relatively small predator and pulling its feathers inward and narrowing its eyes for camouflage when faced with a larger one), and the Northern Hawk Owl (one of the few owls that is only active during the day). List of ineligible candidates: Spotted Owlet, Little Owl, Forest Owlet, Burrowing Owl, A. megalopeza, A. veta, A. angelis, A. trinacriae, A. cunicularia, A. cretensis

Kingfishers

Kingfishers are a group of often brightly-colored birds that have dagger-like bills and short legs. They are predatory and most species hunt by watching from a perch. When prey is spotted, they swoop down to catch it in their bill before beating it to death against a hard surface. Though some kingfishers do indeed eat fish, many species primarily feed on land animals. They have keen eyesight, and species that fish are able to account for the effects of water refraction and reflection when diving for prey. Most kingfishers nest in burrows, though some use tree holes or dig cavities in termite nests. Highlighted species include the Shovel-billed Kookaburra (a large kingfisher with a uniquely short, broad bill), the Common Kingfisher (well-recognized kingfisher found widely across Eurasia and Northern Africa, has a greenish-blue or blue body), the Guam Kingfisher (extinct in the wild, only surviving birds are in a captive breeding program), and the Pied Kingfisher (known for commonly bobbing its head and flicking its tail when perched as well as hovering while searching for prey, often groups in large numbers at night to roost). List of ineligible candidates: Rufous-Bellied Kookaburra, Spangled Kookaburra, Blue-Winged Kookaburra, Laughing Kookaburra

Toucans

Toucans are a group of tree-dwelling birds most notable for their very long and slender bills, which contrast heavily with their, in general, short and compact bodies. Their bills are very colorful, with their light weight allowing the birds to hold them up, given their tiny bodies and short necks; they also have serrations which aid in feeding on fruit that can’t be reached by other birds. In addition, the bills are great for thermoregulation, allowing the toucans to release heat from the bill. They also might use the large bills to actually intimidate other birds and steal eggs and babies from their nests. They have very long tongues - like their close relatives the woodpeckers - that allow them to find food deep in trees. Their tails are also highly adapted - with the vertebrae fused and attached with a ball and socket joint, allowing the tail to jut forward towards the head. They are very social birds in the tropics, and they may fight with their bills and chase each other while they digest food. Highlighted species include the Toco Toucan (the largest and arguably best known toucan, has a black body and brightly colored beak), the Curl-crested Aracari (has a distinct short crest of curled feathers along the top of its head), and the Plate-billed Mountain Toucan (known for two distinct colorations between the northern and southern members of its species, northern toucans have brown eyes and orange on the upper beak while southern toucans have violet/green eyes and yellow and pink on the upper beak). List of ineligible candidates: None

Falcons

Falcons are a group of diurnal birds of prey. They are not closely related to the Accipitrids, despite their similar appearance and lifestyle. As with other birds of prey, the females are typically larger than the males. Most falcons are fast fliers that strike their prey quickly in flight before dispatching it by biting. A tooth-like projection on their upper bill helps them deliver the coup de grâce. The caracaras are an unusual group of falcons that fly relatively slowly and often forage by scavenging. Highlighted species include Gyrfalcon (the largest known falcon which mostly, but not exclusively, lives in the tundra and mountains), the Pygmy Falcon (one of the smallest raptors known which feeds on small animals in the dry bush of Africa), the Red-throated Caracara (unique for being a bee- and wasp-eating caracara, hunts in small groups in jungle lowlands), and the Mauritius Kestrel (an extremely distinct, island-dwelling kestrel that was very close to extinction, but has since been successfully raised back up so that it is “only” endangered, with conservation efforts still ongoing). List of ineligible candidates: Peregrine Falcon

Cockatoos & Cockatiels

Cockatoos are a group of parrots which, though not as colorful as other parrots, do make up for it with extensive crests on their heads that are used for display. They also have extensively curved beaks and are, usually, larger than other parrots, with the Cockatiel being a notable exception. Extensively intelligent birds, they are highlight social and roost and travel together in large and noisy flocks, and are extremely curious birds, often kept as pets (for better or, more often than not, worse) or even regarded as pests when it comes to human crops. Feeding mainly on plants, they forage together in tight flocks to protect themselves from various birds of prey that attack them. They nest in holes in trees, and are primarily known from Oceania. Highlighted species include the Galah (a pink cockatoo that is extremely common and can often be seen in groups foraging in the Australian countryside), the Cockatiel (the smallest species, known for their distinctive crests and bright cheek patches, as well as their status as the second most popular companion bird), the Palm Cockatoo (a large black species with red cheek patches, and potentially the largest known cockatoo and one of the largest parrots in Australia, it also makes many complex vocalizations including the word “hello” and males perform drumming displays to establish territories), and the White Cockatoo (a rather charismatic and noisy bird that, honestly, the only thing I’m going to leave you with here is this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRsfOGJ5lZg). List of ineligible candidates: None

Lyrebirds

The lyrebirds are a group of perching birds adapted to life on the ground that are most notable for their ability to mimic almost any sound in their environment. Male lyrebirds also have long, elaborate tails, that are used to display for mates. For a long time, these birds were thought to be more closely related to things like pheasants and junglefowl; however, when their chicks were found and seen to be more like those of other perching birds, they were quickly reclassified. Lyrebirds mimic the sounds of things they hear around them - from koalas, to kookaburras, to chainsaws and camera shutters - and use them in their extensive songs, and they have the most intricate vocal musculature known in any perching bird. The three species are Albert’s Lyrebird, the Superb Lyrebird, and one extinct species, M. tyawanoides. They differ primarily in that the Superb Lyrebird is significantly larger and one of the largest known perching birds in general, and Albert’s lyrebird is much rarer. In addition, Albert’s Lyrebird lacks the extensive tail-fan of the Superb Lyrebird. The one extinct species, M. tyawanoides, is known from the famous Riversleigh Environment of Miocene Australia, showing that this group was already around about 23 million years ago, and may have been more diverse than what is shown in its living members. M. tyawanoides was smaller than either living lyrebird. List of ineligible candidates: None

Birds of Paradise

Birds of Paradise are some of the most beautiful and weird perching birds known, with a wide variety of extremely specialized and colorful display feathers, as well as very elaborate display rituals that they use to signal to each other during mating. They are also highly sexually dimorphic, with the males having these extensive bright plumages and the females generally looking rather drab in comparison. They come primarily from Oceania - Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and Australia - and they live primarily in rainforests. They eat primarily fruit and some arthropods, and though many of them are monogamous, some do change mates with large congregations of males competing against each other for females. These competitions not only display their plumages, but also usually features extensive dancing and weird behaviors based on the plumage itself. They also often hybridize between the species, which makes classifying many of these birds sometimes difficult. Highlighted species include Wilson’s Bird of Paradise (the males of which have curly tail feathers and extensive coloration on their backs, and they clear an area of the rainforest to display to a female, conducting a very elaborate mating dance that can be seen in Planet Earth II), the Greater Bird of Paradise (the largest bird of Paradise with extensive, fluffy plumage coming out of the tail in the males, as well as iridescent green feathers), the Victoria’s Riflebird (whose males display blue feathers on their throat and curve their wings, moving in a jerky fashion from side to side, before the female sort of mimics by raising her wings, until they finish dancing and actually kind of hug with their wings before copulation), the Raggiana Bird of Paradise (in which the males also have fluffy feathers coming out of their back and tail, and display by clapping their wings and shaking their heads), and the King of Saxony Bird of Paradise (in which the males have very long, striped, ribbon like feathers coming out of their head). List of ineligible candidates: None

Mockingbirds & Thrashers

The mimids - mockingbirds, thrashers, tremblers, New World catbirds, and relatives - are a group of songbirds that are noted for their mimicry, as demonstrated by the name “mockingbird”. They are usually gray and brown in color, with bigger tails and longer beaks than their close relatives, and are also in general large for songbirds. They have long legs that allow them to hop through their environment and feed on small insects and fruit, and they live in a wide variety of habitats around the Western Hemisphere. In general, they are very active, loud, and aggressive birds. Highlighted species include the Northern Mockingbird (a North American species that sings fairly constantly, can recognize individual humans, and is a wee bit of an asshole), the Galápagos Mockingbird (one of the four types of Mockingbirds from the Galápagos Islands that eats seal placentas… as well as more mundane things, and helped Darwin in understanding natural selection), and the Gray Catbird (which makes a mewing sound like a cat, and also mimics calls made by other birds). List of ineligible candidates: None

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congress Sends Trump Tax-Cut Bill in First GOP Legislative Win

House Republicans passed the most extensive rewrite of the U.S. tax code in more than 30 years -- hours after the Senate passed the legislation -- handing President Donald Trump his first major legislative victory.

The chamber’s 224-201 party line vote on Wednesday -- a redo thanks to a procedural hiccup -- sent a bill to the president that provides a deep, permanent tax cut for corporations and shorter-term relief for individuals. Not a single Democrat in either chamber voted for the measure.

The legislation, which has scored poorly in public opinion polls, promises to become one of the biggest issues in the 2018 elections that will determine whether the GOP retains its majorities in Congress.

“I think minds are going to change and I think people are going to change their view on this,” House Speaker Paul Ryan, a Republican from Wisconsin, told ABC’s “Good Morning America” before the vote Wednesday. “The average taxpayer in every income group is getting a tax cut.”

The vote was a triumph for Ryan, a self-described policy wonk who put aside his vision for a more comprehensive, cutting-edge -- and controversial -- approach to overhauling corporate taxes earlier this year. In the end, Ryan oversaw compromises that trimmed some personal deductions and settled for temporary individual tax relief to help cover the cost of the deep corporate tax cut.

“I promised the American people a big, beautiful tax cut for Christmas. With final passage of this legislation, that is exactly what they are getting,” Trump said in a statement. “By cutting taxes and reforming the broken system, we are now pouring rocket fuel into the engine of our economy.”

The United States Senate just passed the biggest in history Tax Cut and Reform Bill. Terrible Individual Mandate (ObamaCare)Repealed. Goes to the House tomorrow morning for final vote. If approved, there will be a News Conference at The White House at approximately 1:00 P.M.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 20, 2017

The House took its second vote on the bill in two days after Senate Democrats forced their GOP counterparts to make three relatively minor changes to the bill -- including dropping a provision that had named it the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Under congressional rules, the House and Senate must approve the same bills.

Other changes were related to provisions allowing parents to use 529 educational savings accounts to cover expenses of home-schooling their children and subjecting certain private universities’ endowments to a new excise tax.

“The only thing better than voting on tax cuts once is voting on tax cuts twice,” House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady, a Texas Republican, said Tuesday.

The Senate passed the legislation on a party line vote just before 12:45 a.m. on Wednesday. Trump marked the occasion on Twitter, calling the legislation “the biggest in history Tax Cut and Reform Bill” -- though experts have said that’s not the case.

The White House is planning to hold a “bill passage event” with House and Senate members at 3 p.m. But the gathering won’t be a signing event, which will happen at a “later date,” White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said in an emailed statement.

SALT Controversy

“For the first time in more than three decades, we cleared a comprehensive overhaul of the nation’s tax code and delivered on our promise of creating and advancing pro-growth policies,” said Senator Orrin Hatch, the Utah Republican who chairs the tax-writing Finance Committee.

The bill slashes the corporate tax rate to 21 percent from 35 percent, enhancing the U.S. position against other industrialized economies, which have an average corporate rate of 22.5 percent. It offers an array of temporary tax breaks for other types of businesses and for individuals -- including rate cuts that will tend to favor the highest earners. Most middle-class workers will also get short-term relief, but independent analyses show the amounts aren’t large.

The average tax cut for the bottom 80 percent of earners would be about $675 in 2018, according to an analysis by the Urban Brookings Tax Policy Center. The top 1 percent of earners would get an average cut of about $50,000 that year, and the top 0.1 percent would get an average of $190,000, according to the group’s analysis.

Some middle-class families could see hikes because of changes to the so-called SALT deduction, which provides a tax break on state and local property taxes as well as income taxes or sales taxes. The provision to cap those deductions at $10,000 proved to be one of the most contentious for House Republicans from high-tax states. GOP lawmakers in New York, New Jersey and California have objected to limiting the deduction, saying it might hurt them politically.

In Tuesday and Wednesday’s House vote, only 12 Republicans -- all but one of them from those three states -- voted against the measure.

Spending Side

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell predicted that the changes would gain favor with voters who have so far been cool to the legislation in polls.

“If we can’t sell this to the American people, we ought to go into another line of work,” he said during a news conference after the Senate vote.

The changes would reduce federal revenue by almost $1.5 trillion over the coming decade -- before accounting for any economic growth that might result, according to Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation, which analyzes tax legislation. Earlier versions were forecast to increase deficits by roughly $1 trillion even after any growth effects.

Asked whether the tax plan will add to the deficit, Ryan said, “We need to keep focused on the spending side of the ledger as well.” He said in the coming year, Congress will be focused on giving states more flexibility with Medicaid and on “getting people from welfare to work.”

Obamacare’s Heart

In one of the tax measure’s most controversial provisions, GOP senators attached language that repeals a major piece of the health-care legislation: the individual mandate that requires people to have insurance coverage.

“It’s not a total replacement, but it takes the heart out of Obamacare,” McConnell said in an interview Tuesday before the Senate vote.

GOP leaders say the Obamacare mandate’s penalty -- $695 for individuals -- falls disproportionately on lower- and middle-income people. Repealing it is estimated to generate roughly $300 billion over 10 years, helping to keep the tax bill from creating even larger potential deficits. But at the same time, about 13 million people are expected to drop their insurance coverage over that decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate.

Some health economists say the change would lead to higher health-coverage premiums, perhaps canceling out the effect of the individual tax cuts for many. Some GOP lawmakers, including Senator Susan Collins of Maine, are seeking legislation to help stabilize the situation, but the fate of those efforts remains unclear.

McConnell said Tuesday he would offer such provisions in a spending bill “later in the week.”

‘Crumbs and Tax Hikes’

Collins, a moderate, also won concessions that expanded a deduction for medical expenses for two years and preserved a partial individual deduction for state and local taxes.

Overall, the bill has failed to win broad popularity in public opinion polls. Despite Trump’s repeated attempts to sell it as a boon for the middle class, half the public thinks they’ll pay higher taxes under the bill, according to a Monmouth University poll that was released Monday.

Democrats say they’re eager to make the tax bill a major issue in next year’s congressional elections.

“The bill provides crumbs and tax hikes for middle-class families in this country and a Christmas gift to major corporations and billionaire investors,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, a New York Democrat, said Tuesday. “Republicans will rue the day they passed this bill and the American people will never let them forget it.”

More From this publisher : HERE ; This post was curated using : TrendingTraffic

=> *********************************************** Read Full Article Here: Congress Sends Trump Tax-Cut Bill in First GOP Legislative Win ************************************ =>

Congress Sends Trump Tax-Cut Bill in First GOP Legislative Win was originally posted by A 18 MOA Top News from around

0 notes

Text

Trump Says Very Sure Rubio Will Vote Yes: Tax Debate Update

Congressional leaders worked quickly to finalize compromise legislation for floor votes next week in an all-out effort to provide themselves and President Donald Trump with a major policy victory before the end of 2017. Here are the latest developments, updated throughout the day:

Trump Says ‘Very Sure’ Rubio Will Vote ‘Yes’ (3:14 p.m.)

President Donald Trump said he’s “very sure” Senator Marco Rubio will vote to pass tax legislation next week -- despite the Florida Republican’s threat to oppose it unless there are further enhancements to the child tax credit.

“I think that Senator Rubio will be there,” Trump said during a White House event about the administration’s broad deregulation plans. “Very sure.”

Rubio has said he wants more than $1,100 worth of an expanded child tax credit to be refundable -- a measure that would mean larger benefits for working class parents. He and Senator Mike Lee, a Utah Republican, proposed such an expansion earlier this month -- to be paid for by increasing the proposed corporate tax rate less than 1 percentage point -- but their colleagues rejected that provision.

Lee is currently “undecided” on the tax legislation, his office said. He “continues to work to make the CTC as beneficial as possible to American working families,” spokesman Conn Carroll said in an email. -- Sahil Kapur

Rubio Opposes Bill Without Child Credit Boost (2:28 p.m.)

Republican Senator Marco Rubio said he intends to vote against Republican tax legislation as written unless the refundable portion of the child tax credit rises from $1,100, throwing a wrench into conference negotiations.

“I want to see the refundable portion of the child tax credit increased,” the Florida Republican said Thursday. “If it stays at $1,100 I’m a no.”

Rubio and Senator Mike Lee, a Utah Republican, have proposed expanding the credit to make more of it refundable against payroll taxes, a change that would help more working class families.

Republicans have a narrow majority in the Senate, where they passed an initial version of tax legislation with just 51 votes. Losing Rubio’s support would still allow them to pass the final legislation, but would mean that Senate leaders could lose no others.

Earlier this month, senators rejected the Rubio-Lee proposal -- which would have been paid for by setting a slightly higher corporate tax rate. This week, as it became clear that lawmakers were instead considering increasing the corporate rate anyway -- while cutting the top individual income tax rate to 37 percent -- Rubio didn’t hide his displeasure.

On Thursday, he said GOP leaders “found the money to lower the top rate” but “can’t find a little bit” more to help parents raising children.

Senate leaders have said they feel confident they have the votes to approve the bill next week. But Rubio said he has not yet received any assurances on his demand.

The Senate bill would expand the credit to $2,000 per child. Asked if it’d be tough to vote no if he’s the deciding vote, Rubio said, “Not tough at all.” -- Sahil Kapur, Steven T. Dennis

Changes Seen Costing $200 Billion in Revenue (12:25 p.m.)

Tentative details that have emerged on a consensus tax plan would wipe out more than $200 billion in revenue over 10 years -- leaving lawmakers to find additional ways to make up the cost, according to one independent analyst’s calculations.

As a consequence, lawmakers may look to set new time limits on the individual tax cuts they intend to offer, wrote Henrietta Treyz, the director of economic policy for Veda Partners LLC, an investment adviser and consulting group.

Another analyst, Isaac Boltansky of Compass Point Research & Trading LLC, also wrote in a note that earlier sunsets on the individual tax cuts represents one option for lawmakers. Both analysts said lawmakers might also set higher-than-planned tax rates on an estimated $3.1 trillion in foreign earnings that U.S. companies have stockpiled offshore.

The Senate bill would already wipe its individual tax cuts off the books beginning in 2026 to help meet budget constraints. GOP lawmakers have stressed that they believe the tax cuts would continue -- but that would be up to a future Congress to decide.

House and Senate lawmakers are putting the finishing touches on a compromise measure that they hope to send to Trump next week. Tentative changes would include cutting the top individual rate and expanding an individual deduction for state and local taxes -- measures that could easily cost $200 billion to $300 billion over a decade, Treyz wrote.

Lawmakers have also agreed to set a higher corporate tax rate than originally planned, taking the current 35 percent rate to 21 percent instead of 20. That change would generate roughly $100 billion over 10 years, Treyz estimated. But another change -- beginning that new rate in 2018 instead of 2019, as the Senate bill would have done -- will more than consume that revenue savings, she said.

It remains unclear how lawmakers will cover the cost. Under the 2018 budget they approved, the tax bill cannot result in more than $1.5 trillion of deficits over the next decade. The version that the Senate passed on Dec. 2 has been estimated by Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation as reducing revenue by $1.45 trillion over that period.

Senator John Thune, the chamber’s third-ranking Republican, said that officials had many of their plans scored Wednesday night -- but those results haven’t been made public. -- Lynnley Browning

Brady Says State Sales Tax Break Part of Deal (11:05 a.m.)

House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady, who’s overseeing the House-Senate conference committee of tax negotiators, said Thursday that taxpayers will be able to deduct state income taxes or state sales taxes in addition to property levies -- up to a $10,000 cap.

The versions of the bills approved by the House and Senate preserved only the individual deduction for state and local property taxes -- capped at $10,000 -- but not for income or sales taxes.

Meanwhile, GOP lawmakers began to reveal their tentative plans for approving the legislation next week.

House Republicans have been told that the Senate will vote first on the legislation -- perhaps on Monday or Tuesday, said GOP Representative Tom Cole of Oklahoma. Then the House would vote on Tuesday or Wednesday, Cole said.

Before that, Brady said, members of the House-Senate conference committee will have a two-hour window to sign a report on their official agreement on Friday morning. He said he doesn’t know yet when text of that agreement would be released.

But Senator John Thune, the chamber’s third-ranking Republican leader, said Thursday that he expects that an actual bill for the compromise measure will be made public on Friday. -- Laura Davison and Erik Wasson

Senate’s Thune Says Bill Text Likely by Friday (10:43 a.m.)

Republican lawmakers are trying to release the text of a compromise bill by Friday in order to hold votes in the House and Senate early next week, said Senator John Thune, the chamber’s third-ranking Republican.

Lawmakers last night had various changes to the legislation analyzed for their revenue effects, Thune said Thursday. “I would say it should be out there tomorrow, we need to have text out there tomorrow so we can vote on it Monday, Tuesday,” he said.

If they stick to that pace, legislation could be delivered for President Trump’s signature by mid-week next week. -- Ari Natter

What to Watch on Thursday

More details of the final legislation may emerge as lawmakers float trial balloons, count votes and prepare to release their plans on Friday.

The plan may be tweaked as lawmakers receive “scores” of various proposals that gauge how much revenue they’d produce or cost.

One sticking point that remained Wednesday was whether to permanently double the threshold at which the estate tax applies -- meaning that the levy would apply to fewer multimillion-dollar estates from now on. The Senate had earlier voted to double the exemption -- currently about $11 million for a married couple -- but only until 2026.

Another centered on how quickly to phase out a provision that would allow companies to fully and immediately deduct the cost of their equipment purchases. More clarity may emerge on both measures Thursday.

Here’s What Happened on Wednesday

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen downplayed the economic growth effect that would result from the tax overhaul. “It’s not a gigantic increase in growth,” she said during a news conference.

Lawmakers haven’t finalized the rates that U.S. companies would pay on an estimated $3.1 trillion in earnings they’ve stockpiled overseas -- and those rates may change depending on the final bill’s revenue score, said Representative Tom Reed, a Republican member of the tax-writing House Ways and Means Committee.

Trump promised everyday Americans a “giant tax cut for Christmas” during a speech that the White House billed as his closing argument for the tax legislation.

More From this publisher : HERE ; This post was curated using : TrendingTraffic

=> *********************************************** Read More Here: Trump Says Very Sure Rubio Will Vote Yes: Tax Debate Update ************************************ =>

Trump Says Very Sure Rubio Will Vote Yes: Tax Debate Update was originally posted by A 18 MOA Top News from around

0 notes

Text

Retailers Are Hoping For the Best Christmas Sales Since the Recession

With consumer spending surging, retailers are hoping for something they haven’t seen since the last recession began a decade ago: a truly great Christmas.

The Commerce Department reported better-than-expected U.S. retail sales for November and revised its October figures upward, bringing a fresh wave of optimism to a long-embattled industry.

Holiday shoppers are snapping up Nintendo Switch devices and Fingerlings toys as their disposable income grows, according to Craig Johnson, head of the Customer Growth Partners. His research firm just boosted its forecast for holiday sales to 5.6 percent, well above the 4.3 percent it had targeted earlier.

“We think this marks the beginning of a real and sustained rebound,” Johnson said in an interview. After tracking the 50 largest retailers across 90 major shopping venues, he believes that spending will grow more this season than in any holiday since before the Great Recession began in 2007.

“It’s all demographics, and it’s geographically widespread,” he said.

Austin Kreitler, a 21-year-old college student in New York, is one shopper who is ready to open his wallet this holiday season.

“I definitely spent more this year than I have in previous years,” he said during a visit to Bloomingdale’s in Manhattan. “I got some novelty things, but I also got my mom a pearl necklace and earring set.”

E-Commerce Growth

The spending uptick is good news for retailers of all stripes, but some are faring better than others. Online spending growth is expected to outpace brick-and-mortar expenditures, and plenty of companies are still struggling.

Pier 1 Imports Inc., the home-furnishings chain, saw sales weaken in the first two weeks of December. The slow start to the holiday season weighed on the company’s fourth-quarter forecast, sending the shares on their worst rout in almost three years Thursday.

Traditional retailers are increasingly chasing online dollars. Wal-Mart Stores Inc. has acquired web brands such as Jet.com and Bonobos, and it’s offering two-day free delivery to entice shoppers. Target Corp., meanwhile, agreed to buy e-commerce startup Shipt Inc. this week for $550 million, aiming to challenge Amazon.com Inc.

The greater emphasis on online orders may be one reason why a rosier holiday season isn’t translating into traffic gains at many malls. During Black Friday, foot traffic was down slightly for the second year in a row, according to data compiled by Prodco Analytics and Bloomberg.

Genevieve Domingo, a shopper who was trying on boots at Bloomingdale’s, said she’s getting most of her gifts online this year, including a Game of Thrones drinking horn and a DNA kit for her brother.

Broad Gains

Merchants without physical stores saw their biggest sales gain last month since October 2016, the Commerce Department reported on Thursday. But retail growth was broad-based, with 11 of 13 categories posting increases. Apparel sales had their third straight uptick, the longest such stretch since mid-2014.

The numbers indicate that household spending, which accounts for about 70 percent of the economy, is picking up during the final stretch of the year. The job market remains strong, with solid hiring and an unemployment rate that’s the lowest since December 2000. In addition, stock-market gains and rising home values are boosting household wealth.

If this season’s sales reach Customer Growth Partners’ target, it would be the best holiday performance since 2005. The industry posted a 6.1 percent increase that year, when the economy was still booming and a red-hot housing market was fueling spending.

Tax Cut?

One wild card is the tax bill wending its way through Congress. The legislation promises to to lower the burden for households by doubling the standard deduction, but consumers who can’t withhold as much of their state and local taxes could lose some spending power.

The National Retail Federation, the industry’s biggest trade group, has argued that consumers are spending more this season because they anticipate a tax cut. About 174 million Americans shopped during the long Thanksgiving weekend, 10 million more than expected, the organization said.

“All in all, it’s really portending for a very solid and maybe one of the best holiday seasons that we’ve seen in years,” Jack Kleinhenz, the NRF’s chief economist, said in an interview. “We’ll have to wait and see how December plays out.”

More From this publisher : HERE ; This post was curated using : TrendingTraffic

=> *********************************************** Learn More Here: Retailers Are Hoping For the Best Christmas Sales Since the Recession ************************************ =>

Retailers Are Hoping For the Best Christmas Sales Since the Recession was originally posted by A 18 MOA Top News from around

0 notes

Text

Roy Moore almost certainly isn’t going to be a senator

(CNN)If you thought Roy Moore's political future couldn't get any more bleak after four women went on the record with The Washington Post alleging that the Alabama Republican Senate nominee sought relationships with them when they were between 14 and 18, today showed things could get worse for Moore. Much, much worse.

"Mr. Moore attacked me when I was a child," Nelson said, recounting that Moore was a regular customer at a restaurant where she worked as a waitress when she was 15 and 16. She described a harrowing chain of events that ended with Moore attempting to force her into a sex act in a parked car -- an episode that, she said, left her with severe bruising on her neck.

Perhaps the most devastating moment of the press conference, however, was when Nelson produced her 1977 high school yearbook that including this inscription: "To a sweeter more beautiful girl I could not say 'Merry Christmas' Christmas 1977 Roy Moore, D.A. 12-22-77 Olde Hickory"

Through a spokesman, Moore dismissed the allegation.

"Gloria Allred is a sensationalist leading a witch hunt, and she is only around to create a spectacle," Moore campaign chairman Bill Armistead said.

But it's hard to dismiss the damage done here.

What Nelson is alleging is sexual assault, not sexual misconduct. One of the four women in the Post story was 14 at the time she encountered Moore, which is below the official age of consent -- 16 -- in Alabama. The others were between 16 and 18 and said the encounters were consensual. Moore was in his early 30s at the time.

Moore's defense to this point has been that the women quoted in the Post story were somehow cajoled into lying about their encounters with him -- fake news and all that.

That defense completely overlooked the fact that all four women allowed the Post to print their names. None of the four women knew one another. None of them reached out to the Post in hopes of having their story told. The Post spoke to more than two dozen witnesses who knew Moore between 1977 and 1982 -- when these instances allegedly took place -- and corroborated the facts as the women relayed them.

Now, Nelson adds her name to that list. Like Leigh Corfman, who alleged that Moore touched her -- and urged her to touch him -- when she was 14, Nelson said she voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 election. Which makes it difficult to cast this as some sort of politically motivated gambit.

To believe Moore's denials at this point, you must also believe that:

1. All five of these women, who say they have never met one another, are not only all lying but doing so in a coordinated manner with remarkably similar stories of Moore's pursuit of them.

2. The dozens of corroborating witnesses that the Post spoke to are also part of a broad -- and very well-organized -- conspiracy to keep Moore from the Senate.

3. Nelson forged -- or had someone forge -- an inscription on her 1977 high school yearbook from Moore, OR Moore signing a teenage girl's high school yearbook -- and noting she was "beautiful" -- was entirely innocuous.

Are there people in Alabama -- and nationally -- that believe all of those things? Sure. But it appears that Republican Senate leaders are not among them.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell told reporters in Kentucky Monday morning that the time had come for Moore to "step aside." Then, even as Nelson's press conference was wrapping up, Colorado Sen. Cory Gardner, who heads the party's campaign committee, released a statement calling on Moore to be expelled from the Senate if he manages to win the special election on December 12.

"If (Moore) refuses to withdraw and wins, the Senate should vote to expel him, because he does not meet the ethical and moral requirements of the United States Senate," Gardner said.

President Trump, who continues to travel in Asia, has not said much of anything on Moore's situation -- insisting that he has been too busy to focus on the allegations. But Trump returns to Washington on Wednesday and may be pressured to say something even sooner than that by way of clarifying where his White House comes down on Moore.

Regardless of what Trump says, however, it's hard to see how Moore ever actually holds a Senate seat. Gardner's pledge to vote to expel him if he wins means that such a motion would almost certainly pass. What senator -- Democrat or Republican -- could or would vote against expelling Moore at this point?

If past is prologue, Moore will continue in the race -- arguing that this is all just one big conspiracy by, well, everyone, to get him. But, it seems clear now that no matter what Moore does, his chances of becoming a senator are increasingly minuscule.

More From this publisher : HERE ; This post was curated using : TrendingTraffic

=> *********************************************** See More Here: Roy Moore almost certainly isn’t going to be a senator ************************************ =>

Roy Moore almost certainly isn’t going to be a senator was originally posted by A 18 MOA Top News from around

0 notes

Text

Toys R Us Plans Bankruptcy Filing Amid Debt Struggle

Toys “R” Us Inc., which has struggled to lift its fortunes since a buyout loaded the retailer with debt more than a decade ago, is preparing a bankruptcy filing as soon as today, according to people familiar with the situation.

The Chapter 11 reorganization of America’s largest toy chain would deal another blow to a brick-and-mortar industry that’s already reeling from store closures, sluggish mall traffic and the threat of Amazon.com Inc.

Filing for bankruptcy would allow Toys “R” Us to restructure $400 million in debt that comes due next year, potentially letting the chain rebuild as a leaner organization. The retailer has hired a claims agent, which typically helps with administering such a process, people with knowledge of the situation said last week. And its vendors have been curtailing shipments amid concern that Toys “R” Us might not be able to pay its bills.

“This filing is really a buildup of financial problems over the past 15 years,” said Jim Silver, an industry analyst and the editor of toy-review site TTPM.com. “Finally, the straw broke the camel’s back.”

With speculation of a bankruptcy mounting, shares of Toys “R” Us’s vendors tumbled on Monday. Mattel Inc., the maker of Barbie and Fisher-Price, fell 6.2 percent -- its worst decline in seven weeks. Shares of Hasbro, the company behind Monopoly, Nerf and Transformers, dropped 1.7 percent.

A representative for Toys “R” Us declined to comment.

Bankruptcy Financing

JPMorgan Chase & Co., Barclays Plc, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. are said to be vying to provide financing for Toys “R” Us while it goes through bankruptcy. Reorg Research said earlier Monday that a filing could come as soon as today.

The debtor-in-possession loan -- known as a DIP -- could be as much as $3 billion, a person with knowledge of the discussions said.

Ratings agencies have rushed to cut their credit ratings on Toys “R” Us to reflect the sinking market sentiment, indicating just how rapidly things have unraveled at the retailer. S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings both downgraded the toy seller Monday, citing media reports and market data pointing to an increased possibility of a broad restructuring. S&P cut its rating to CCC-, the third-lowest level. It had the retailer rated B- just two weeks ago, and Moody’s Investors Service still has a B3 rating and stable outlook for the name.

Much of the toy supplier’s debt is the legacy of a $7.5 billion leveraged buyout more than a decade ago. In 2005, Bain Capital, KKR & Co. and Vornado Realty Trust loaded Toys “R” Us up with debt to take it private. Since then, the Wayne, New Jersey-based chain has struggled to dig itself out.

Interest Expenses

Some years, the company had to spend as much as half a billion dollars on cash interest expenses alone, according to Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Noel Hebert. That left Toys “R” Us with less cash to put toward store expansions, merchandising, and -- crucially -- the growth of its online presence.

“With these debt levels, how much actual flexibility do you have in this environment?” asked Charles O’Shea, who covers Toys “R” Us for Moody’s Corp. “You have to invest online -- because your principal competitors there are really good -- and you’ve got to deal with the debt load and your maturities on top of that. The pie is only so big.”